Vintage_Mania

Bachelor Dog

- Joined

- Apr 11, 2012

- Messages

- 11,625

- Reaction score

- 3,523

- Location

- Eersterivier

- Bike

- Triumph 900 Scrambler

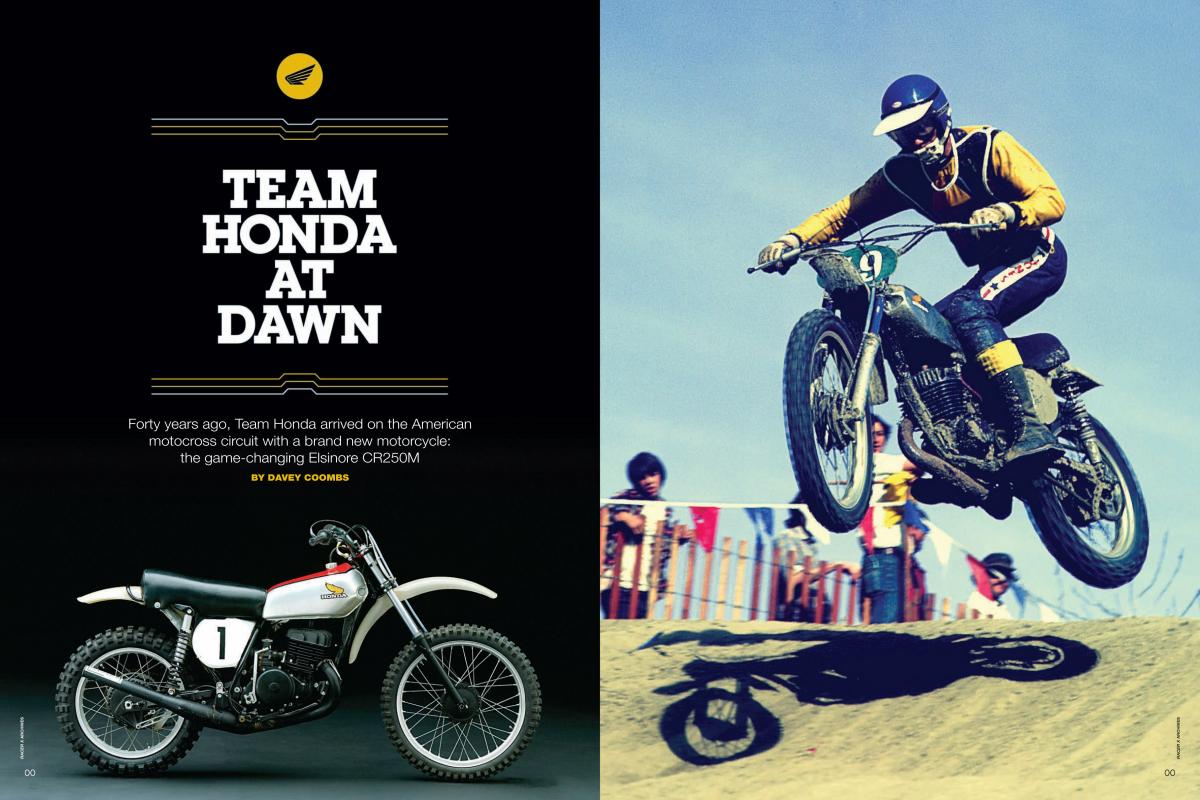

At one time or another, you’ve sat around with your friends and jabbered about the mythical “composite” motorcycle. You know the one -it’ got the peak horsepower of a breathed·on Pursang, combined with the low-end grunt of a Stiletto. It`s got the plush forks of a Maico, turns like a CZ and tracks like a cut-frame Husky. It weighs less than a good 250 and has the punch of a 400. And the best part-you don’t have to do anything to the bike. just ride it like it was a 350 Honda pseudo-scrambler.

We’ve all dreamed about that kind of a machine, but up until now, it never existed.

A quick look around at the competition mounts of the Staff of DIRT BIKE shows what has to be done to make a motorcycle “right” for competition. No one but a fool rides a Maico in stock trim. Different filters, rims and assorted bozos are a must for the serious rider.

Same with thc CZ. Shocks, seals, filters, light components, spokes, etc. Hell. we know what we have to do to our own bikes, and we do it because that’s what must he done.

But we’d rather not.

Not really.

If we never had to replace another wheel with a trick rim.,we would do a dance of joy. Only the Sprocket Spirits know how many stock shocks are gracing the DIRT BIKE garage, gathering dust like an unopened can of FE Plus.

We know that the only way our bike’s perform to our satisfaction is to modify them ourselves. Or con a Friend into the job under the guise of a tech article.

But, like we say. we’d rather not have to do it.

Now, take a deep breath and sit back. You don’t have to do anything of consequence on the new 250 Honda two-stroke racer. Oh sure, there are little things that can be jiggled around to suit the rider, but the package is there and it’s right from the beginning.

No shock changes needed.

Forks are top quality.

Ditto for bars, grips. filter, pegs, controls, etc.

This is really one of the most frustrating goddamn motorcycles we have ever tested. It is so stunningly right as-is that the mind wobbles. And the most important two things to any racer are there: It handles and it’s fast. Faster than anything else in the 250 class. That’s right faster than your buddy’s Pursang and your other pal’s CZ. The only bikes that are going to stay with it (rider skill excepted) are highly modified top-of-the-line 250s. It will pull right alongside most 400s and beat many of them in a point·t0·point drag race.

Quite frankly, we started off on the wrong foot with Honda on getting the bike for a test. Some time ago, they called us and asked us if we wanted to test ride the new trick racer. Tell us when, where and how. etc. It turned out that the “test” was to be an hour or so of riding at Indian Dunes, and that’s it.

Many magazines jumped at the chance to be in print early, and accepted the bike on this basis. We refused, because we feel that we must have a machine and ride it for a number of riders-not just a

low hot laps around the Dunes-to fully understand what the bike is about.

So, Honda was mad at us and we were mad at Honda. Not the best of situations for testing the most newsworthy machine in years.

One, cooler head prevailed. George Ethridge, the honcho at American Honda R&D, eventually got it set up where we could have the Honda Elsinore for an extended period of time and get to know the bike on more intimate terms. The perverted Staff of DB takes nothing for granted.

We met George at the Dunes for the first riding session and our tentative deflowering of the Honda.

We were skeptical-even more so when George hovered about the bike like a Mama Quail protecting her brood. As time went on we found out that George is like that all of the time with the Honda. He loves it dearly. Every time we sat down to talk about the bike, he became misty eyed. Its sort of understandable. What the bike is stems largely from George’s enthusiasm and underlying attitude. George and Mr Sato (the engineer dirt freek in Japan) got together and decided to make a no compromise racer. They both felt that the market would retch if one more street/dirt racer was introduced.

After the usual briefing/familiarisation/question/answer period, we lit the Elsinore up. It started quickly and made us jump back several feet. Even then, we could tell it was for-real engine. revs built quickly with the merest tweak of the right hand. Super-sensitive. Much like a 400 Suzuki. We let the bike sit and idle for the warm up.

This took a long time, as the Honda is ultra-cold-blooded. Attempt to ride it before it’s completely warmed up and the bike will either stall or turn into a freaky monster; we’d say that at least a full five minutes are required before the bike will run clean and smooth.

But it actully did sit there and idle while warming up. Just like their 250 four-stroker. And that’s about all the two stoke had in common. Other than some bits and brackets.

Seat height is so low, that it is possible for a 5’8″ rider to stand flat-footed on the ground and still have a gap between his crotch the

saddle.

As you sit there waiting for the bike to warm up, you’ll notice that everything is well thought out. Controls are shaped right and easy to actuate. Pegs are tucked in close and have the proper saw-toothed serrations, Bars feel good, and at 33 inches, should be wide enough for most everybody.

Squeeze the clutch in ( lightest pull we ever experienced on a 250) and step on the left side mounted, down for low gear shift lever. No crunch.

Unlike other Honda’s, the clutch starts to engage halfway out in a progressive manner. By contrast, the 250 four-stroke does nothing until it’s almost out, then slams home. Either in or out; reacting like a sticky light switch.

Revs build so quickly. it’s hard to tell much about the torque characteristics at first, and the machine feels spooky light. First impressions are not good.

On that first, very first, lap around a course, one feels that the Honda is skittery and overly responsive. Acceleration is staggering. As the shift lever is prodded and the throttle turned, the rider is slammed with huge thrusts of forward motion. Shift up and do it again. Before one realises what is happening the bike is in fifth and the bike/rider combination is approaching 70 miles an

hour. Frightening.

A stab at the brakes to calm the bike down results in smooth, powerful stopping. Your sweat will pass you up. Fifteen minutes if hard riding will have you talking to yourself. “Whew! The damn thing is fast, but man, I’m all over the place. One correction after another, Sure wasn’t a smooth ride-bounced around alot, but the shocks and forks felt good.”

Most of the test riders came away with this initial impression. But after they rested a while, then put some more time on the bike, they started to understand the machine. And when they understood it, the bike began to work. It will take a motocross rider of better than average skill several hours of hard riding before he begins to ride the bike as it should be ridden. If the rider takes the time to do this, he usuall comes back babbling good words about the machine.

Strangely, this is the same way most riders react to a “work” machine. It takes time to get used to the responsiveness. Here at DIRT BIKE, we’ve had the opportunity to ride a number of factory bikes, including the 450 Kawasaki of Brad Lackey. This machine was even harder to get used to, because of the tremendous power output and the light weight.

The more you ride the Honda, the faster you go. And the faster the hike goes. the more stable it feels. Even in the corners.

With an outrageously long 57- plus-inch wheelbase, one would expect the Honda to be ponderous through the turns.

Not so.

Directional changes are ludicrously easy. Perhaps much of the ease of turning comes from the light weight of the bike. Add 30 pounds of garbage to the Honda and it might, indeed, turn sluggish. But

this is of little matter, because the machine works just fine in the corners as is.

The rider can actually change his line while ripping through a turn under full power. All it takes is a weight shift, and at tug at the bars. Once the rider gets used to the light weight of the Honda, he’ll find that he’s snubbing the bike in tighter and tighter on the turns, and driving out earlier.

If the bike is snubbed in too far and the rear end swings out, it does so predictably. Most efficient cornering on bumpy turns is accomplished by getting far forward on the tank and letting the rear end do what it wants to do. It will waggle and hop some, but rarely get out of shape. As soon as the rider is ready to push hard out of the turn, a shift of weight to the rear and heavy throttle straightens the bike out and gets the front end light. Too far back and the bike will get vertical. Weight shifts are very critical and and are the key to riding the Honda quickly.

If you insist on just planting your butt down and staying in one spot, the handling of the bike will not impress you. It will be necessary to clamber all over the motorcycle. A successful Honda rider will look like he has a bad kidney, diaper rash and bugs- all at the same time.

At first, some of the riders thought the Honda was peaky. Ethridge told them to ride the bike like they were attempting to load the engine up. Make it blubber in the taller gears, if you can. This proved to be the secret to riding the CR25o properly. Shift early and make the engine torque.

After we learned to do this. it was possible to take most corners at least one gear higher than we had previously. Some of them two gears higher. Then we would sit back and watch new (first Honda ride)

riders over rev the engine, while we knew the big secret.

The spread of power is astounding, rivalling that of a decent 400.

![Professional First Aid Kit, Trauma First Aid Kit with Labelled Compartments Molle System for Car, Hiking, Backpacking, Camping, Traveling, and Cycling[New Upgrade]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41uCkwNilAL._SL500_.jpg)