Vintage_Mania

1979 Honda CB400T

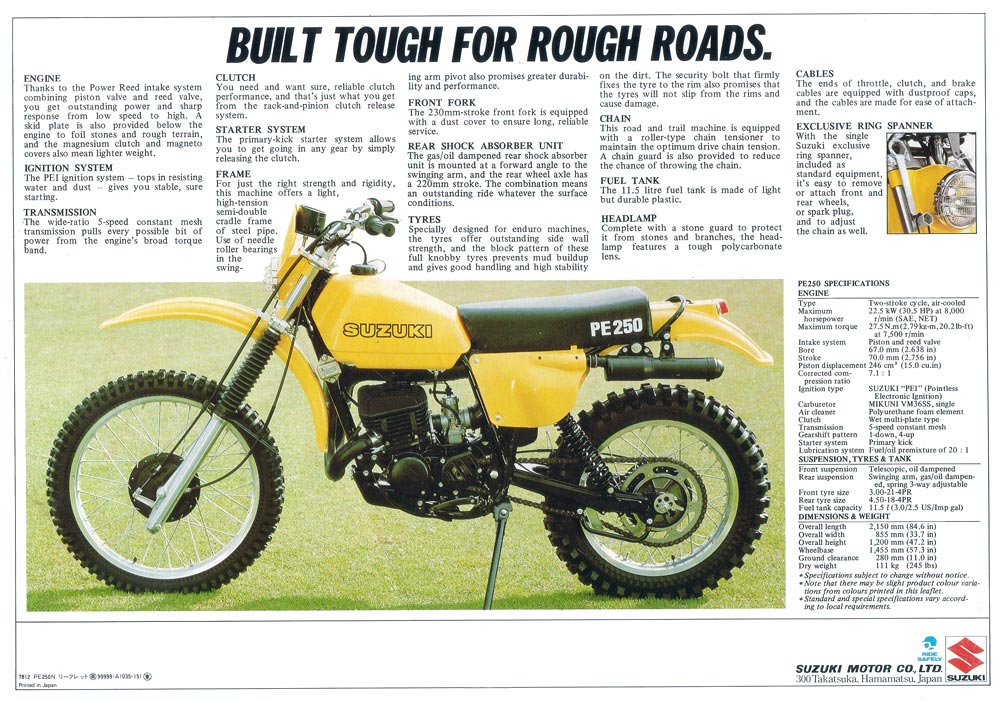

The PE 250 is a much-compromised motorcycle aimed at the largest segment of the enduro bike market. The nucleus of serious enduro and ISDT competitors, a hard-nosed racing fraternity, is vastly outnumbered by the play/trail rider crowd. The enduro/ISDT racers prefer bikes with motocross performance, six-speed gearboxes, firm suspension and razor-sharp handling. These bikes are not supposed to be "fun to ride." The PE 250 was not designed with an emphasis on race level performance, even though it is a descendant of the RM 250B motocrosser. The compromises built into the PE 250 make it an exceptionally appealing enduro/play bike for those not committed to owning a hair-triggered, magnum-powered racer. Suzuki has already displayed its willingness to finalize development before releasing new models. Either that, or they were just plain late. They were the last of the major Japanese manufacturers to introduce motocrossers (the RM series), a high-performance road bike (the GS 750) and finally a real enduro bike. For a year prior to the release of the PE, Suzuki was testing, modifying, racing and perfecting the concept here in the United States. Suzuki has used RM styling features on the PE, but the technical differences between the two are substantial. The aluminum gas tank on the PE holds 3.2 gallons-1.1 more than the RM. It includes a big mouthed filler hole that is nearly an inch larger than the motocrosser’s. The saddle has been changed in both shape and size. Dimensionally the PE seat is 1 1/4 inch lower and 1 inche shorter than the RM saddle. The lightweight internal rotor racing magneto is replaced by a heavier external flywheel CDI ignition with a lighting coil. The six-volt generator is attached to ISDT-type head- and tail lights. A speedometer with reset-to-zero trip meter, front number plate, fork covers, skid plate and brake light switch round out the PE250’s enduro necessities. By using the chassis from the RM 250B, Suzuki eliminated the off times unnecessary and always expensive exercise of designing a brand new frame. The suspension system, however, is the PE’s own. The fork and shocks deliver an inch less travel than the RM, and lower the chassis height a like amount. Spring tension for the front and rear have softer initial and stiffer final compression rates than the RM. Both the PE and RM uses the same 520 D.l.D. chain and 13/50 tooth gearing; internal gearbox ratios are markedly different. The PE’s clutch and straight cut primary gears are the same as used in the , motocrossers.

The PE uses the same crankcase assembly as the RM; special internal milling is needed to provide clearance for some larger gear sets. Later-model PEs will have crankcase castings of their own (which will be used by the RMs) to eliminate the milling process. Cylinder port locations and sizes differ considerably between the two engines. The PE’s intake and exhaust port windows are smaller and shaped differently than those in the RM. The exhaust and transfer windows in the enduro are positioned lower and the intake holes are located higher. The squish volume of the cylinder head has been increased from 27cc to 30.9cc in the PE to compensate for the longer effective compression stroke and to lower the compression ratio. Additionally, an extra spark plug compression release hole is included in the enduro head. The new long stroke engine specifications (67 x 70mm bore and stroke) from the RM 250B are used in the PE, but the motocrosser and enduro crankshaft assemblies are not the same. To accommodate a heavier flywheel on the PE, Suzuki redesigned the shank on the left side crank wheel. The new design incorporates a shorter shank to fix the flywheel closer in for more rigidity and to minimize engine width. Both enduro and race designs are used in the PE’s exhaust and intake systems. The RM expansion chamber is retained. but is fitted with an internal baffle plate. Rather than equipping the PE with an oversize muffler similar to ones used on most enduro bikes. Suzuki designed their own compact, and surprisingly efficient. spark arrestor/silencer. In place of numerous by-pass plates, Suzuki incorporates a nearly full-flow, swirl-type silencer that controls exhaust noise very nicely. The induction systems of the PE and RM are virtually identical. Both bikes use a 36mm Mikuni, the air boxes are shaped similarly and the oiled foam filter elements are the same. The PE has a baffle plate atop the air box to subdue induction drone; the extra intake holes used by the RM are not in the enduro's system. The most marked physical difference between the race- and enduro-model Suzuki's has to do with their ride and seat heights. The saddle height of the PE is lower to permit shorter riders to touch the ground more easily-an aid when paddling in mud or dabbing in rocks. There is a generally muted feeling to the PE250. The suspension is supple and its engine performance is in no way abrupt or otherwise demanding. Its suspension softness is mated to extremely predictable, no surprise handling.

The RM 250B has been widely acclaimed for its superb handling, and the PE has inherited most of the stick- to-the-ground, true-tracking traits of the motocrosser, but not at the expense of a harsh ride. The PE's gently-sprung suspension, low center of gravity and superb ability to secure traction make it one of the best-handling fire-roaders we have ever ridden. Engine performance is what it should be: smooth and usable. Webco’s dynamo meter shows that the PE makes almost 23 bhp, which is one more than Honda’s MR 250 and eight horsepower down on the RM 250B. In comparing the power figures with 250cc enduro-race machines like the Hercules, Can-Am Qualifier or Penton, the Suzuki makes 15 to 20% less bhp and torque. Suzuki has aimed for, and achieved, engine performance which is very similar to Montesa’s V75 and Bultaco’s Frontera enduros. The PE has a noticeable power surge, but not like the explosive charge of the Penton or Can-Am Qualifier, both of which demand cat-like reflexes. ln most any given situation the PE's power is usable because it gets to the ground. Everyone who rode the PE was highly complimentary about the engine’s clean response to throttle variations, broad. useful power range and acceleration. The PE won‘t startle a rider when given the whip, because the engine gains speed evenly and without struggling. ln the lower gears, especially first, the PE will stand up on its back wheel under full throttle-but not without ample notice. Spot-on carburettor jetting allows the bike to be ridden through a wide variety of terrain at half throttle, or less, in higher gears. There‘s no need to keep the engine spinning to maintain momentum. Slogging through rough terrain and topping difficult up hills is one of the PE's specialities. The engine's torque spread. together with the bike's compliant rear suspension, allow the bike to walk over cobbly or steep ground easily. When faced with more challenging terrain the rider can just roll the throttle open and/or go down a gear, and clear obstacles with minimal effort or skill. The engine's smooth power delivery is complemented by near-perfect gear staging. Low gear is right where the rider needs it when attacking demanding inclines. High gear allows for long jaunts at 40 to 60 mph. The middle three gears are spaced close to each other and far from low and top. This means the engine has to make large jumps in getting from first to second and from fourth to fifth. In most situations, the engine's torquey power can handle it.

On very steep climbs and in very soft terrain, however, the rider can sometimes get stuck between gears, because the engine won’t quite jump the ratio span to the higher gear without bogging. In nearly every respect the PE 250 is an excellent cross-country bike. It has enough power and gearing to run close to 70 mph for long periods. The PE's handling is as precise and non-threatening as any enduro bike we have ridden. It does have two undesirables weaknesses: soft suspension and marginal ground clearance. In high-velocity sections where terrain undulations, and road crossings are numerous and deep, the PE's soft ride becomes a liability. A series of rain ruts or whoops will send the Suzuki into a side to side wallow when running hard. When bouncing over tall objects, like boulders, the bottom of the chassis does an unpleasant amount of banging on the tops of the a rocks. Too the marginal ground clearance hampers the bike's performance on rough down-hills, when the front suspension is loaded, by placing the skid plate uncomfortably close to the ground. Riding comfort of the Suzuki enduro is, for the most part, quite good. The thinly padded saddle won't let a rider's buttocks find the seat bottom for two to three hours. A substantial number of riders of all sizes and abilities rode the PE and had mixed opinions regarding the bike‘s lowness. Shorter folks initially commented on the advantage of being able to touch the ground. Compared with tall-riding, long-suspension bikes, they felt more relaxed with the PE’s low-rider stance. When these riders were confronted with a section of large obstacles or rough, fast terrain, however, they complained about chassis bottoming and objects banging off their boots. These traits gave expert- level riders an uneasy feeling. The ISDT type lighting system works acceptably and allowed us to get out of the back country at night on a number of extended riding sessions. However, after 600 miles, the lights retired, victims of vibration and shorted wires. The speedometer’s trip meter is dead-accurate for enduro usage. It is mounted to a steel plate attached to the upper triple clamp. After a few hundred miles the shock and vibration took their toll on the rollers in the speedometer, and the trip meter would stick and jump from a half to a full tenth rather than rolling the digits over smoothly. Mounting the speedo head in a softer cushion would help. The front number plate is also attached to the speedo bracket, and it compounds the vibration problem by fluttering at speeds above 40 mph. Its forward protrusion also leaves it vulnerable to number plate, speedometer and bracket damage in the case of a spill. We destroyed ours in one enduro. Suzuki equips the PE with an ISDT rim protector-type rear tire. It is the same design as the Six Day Barum and Cheng Shin tires. The rubber compound is quite hard, and takes some time before it scrubs-in and loses its slippery feeling. It works best at low pressures-eight to twelve psi. The RM 250A-type Kayaba shocks use nitrogen charged dampers and are good for 300 to 500 miles of non- race use. The spring-loaded chain tensioner works very well to limit lash caused by sloppy adjustment; it remained intact and functional for the duration of the test. The foam air cleaner element is most difficult to remove and replace in the compact air box without knocking dirt down the carburettor throat. The PE 250 does not have all the qualities needed to classify it as an enduro racer or ISDT bike. As is, the PE 250 is an extremely pleasant play/trail bike: a delight to ride and very easy to manipulate. In non-race conditions it offers superb handling, traction and comfort. It isn‘t priced in the bargain basement, as is Honda’s MR 250, but the PE is substantially less expensive than European enduro race bikes. The PE 250 is a middle- of-the-road enduro bike that fits ideally in the hands of trail riders and neophyte enduro competitors who want a friendly. durable, honest and trouble-free dirt bike that will neither thrill them to pieces nor scare them to death.