You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

To the Lungs of the Earth

- Thread starter NiteOwl

- Start date

This site may earn a commission from merchant affiliate

links, including eBay, Amazon, and others.

Just In Time

Pack Dog

On the edge of my seat waiting for the next episode.

NiteOwl

Pack Dog

- Joined

- Dec 31, 2012

- Messages

- 98

- Reaction score

- 0

- Location

- Office Adventurer

- Bike

- Honda XRV 750 Africa Twin

It’s about 500 km from Brazzaville to Pointe Noire, and we’re roughly halfway. How's that for a campsite?

…and a visitor dropped in during the night.

Since 5 AM we’ve heard the odd truck, but there is very little traffic here. We manage a fairly early getaway after getting spotted by a goatherd who wants food for his village. How can we possibly do that?

The RN1 passes by Dolisie, so we just fill up and move on. My wife gets all the attention. It must be the red bike.

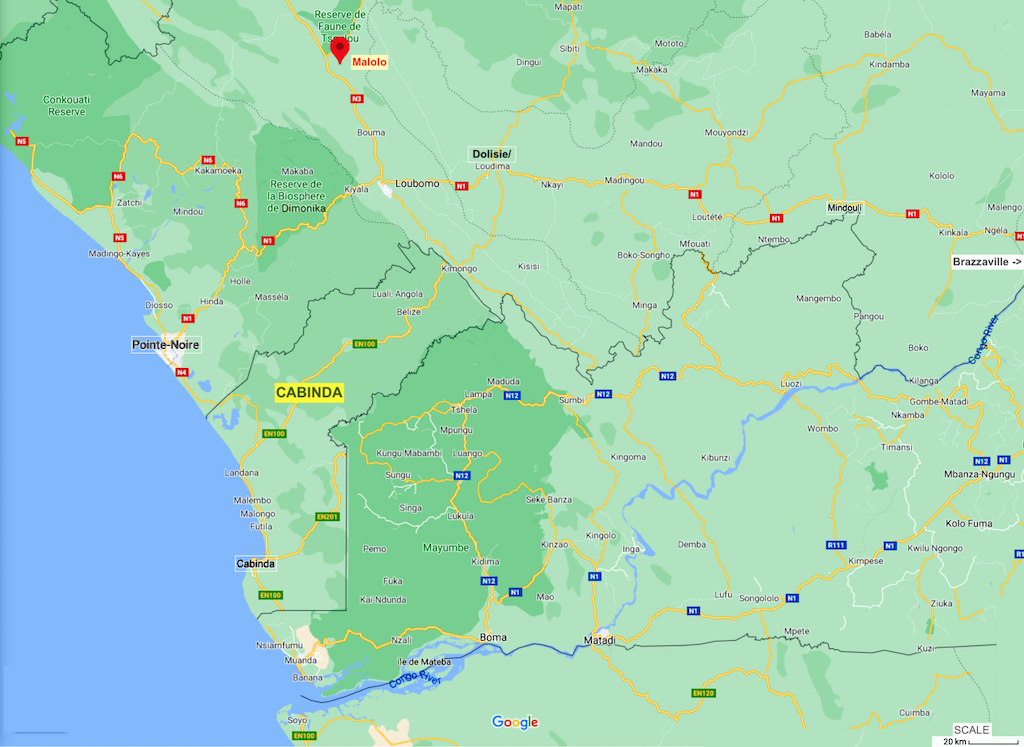

We have a particular interest in this area, as 30 South African families have been given 30 year leases on 1200 hectare farms that were abandoned by the French in the 1960’s at Malolo, 50km north of Dolisie.

It’s a government initiative to reduce their reliance on oil money to pay for imported food, and it started in 2009 when they approached Wynand du Toit (more on him later) to persuade some South African farmers to settle here to help provide food security for the country.

As in much of Africa, commercial farming is a rarity here; most peasants are subsistence farmers who grow just enough for their own needs. It’s 50 km north of Dolisie, which we pass through in the late morning.

Friends of ours were among the lucky recipients in 2011, but it’s a capital-intensive undertaking in a country with almost non-existent facilities of any kind. Without commercial funding, it’s not a viable proposition unless you have plenty of capital. Since they have neither, they have not been able to make the move.

Although we sent emails to our countrymen when we first arrived in Brazzaville, there have been no replies. And we have no phone numbers. So, sadly, we have to pass up the opportunity to drop in. Back home I investigate and it sounds like the whole exercise went sour- by 2014 only 9 farmers were still farming here. Dorsland Trekkers déjà vu?

We come across a few forlorn toll booths. There’s little truck traffic and bikes have free passage. As it should be.

There’s the odd refreshment stall that primarily caters for the passing truck trade. At least the fruit is fresh.

From Dolisie the road passes through the Dimonika Reserve before dropping steeply on the last section, and by lunchtime we start descending the spectacular route down the escarpment.

it’s fantastic riding.

We pull over at a short side road for a bite to eat. A very healthy diet we have here ;-) Buns, sardines, cheese, bananas…

...and two healthy travellers as well.

It starts drizzling as we pull away, and I nearly miss this bushmeat trader:

From a distance, I nearly mistook the pangolin scales for those of a fish. As I ask if I can take a picture, the hostile hunter yells “10 000CFA!”. It seems a bit rich for a photo, but it turns out that this is the price for his pangolin, which is suspended from one hind leg. When I tell him we’re not interested in a dead one, he pokes it in the belly, making it curl up in a defensive ball.

My mind is made up instantly and I pull out a wad of CFA notes. The hapless animal is cut down from the branch and stuffed into a shopping bag. And so we become the owners of a white-bellied pangolin and get entangled in the wildlife trade.

So what is the best option for the survival of this poor animal? If we release him too near his captor, he will be for sale again tomorrow. If we get caught with it, we might face arrest! We carry on for a few kilometres before turning off onto a dirt road towards a school. After making sure we haven’t been spotted, we take the pangolin among the trees to release him. After wriggling out of the bag, he is down a burrow before I can even get a good photo of him (her?). There’s gratitude for you!

Soon afterwards we hit the outskirts of Pointe Noire. It’s mayhem, and we are pretty tired from travelling most of the day.

We pull over to regroup and to locate the coastline, where we hope to be able to find accommodation. It looks like we have to carry straight on and the turn at the harbour. Along the way, some bizarre memorials- how could this small republic possibly have an interest in the World Wars?

We cross the rusty railway lines en route to the beach. The tracks are overgrown and only the wagons on the left look they are still in use.

And suddenly we are at the beach. It’s a sight for sore eyes. At a larny looking restaurant facing the sea the bellhop invites us over, assuring us that we can park at the entrance and the bikes will be fine while we head for the bar. The sight of the sea is worth a small celebration and we plop down.

The view may be great, but it turns out that accommodation here will cost a pretty penny. We decide to look for accommodation a short distance away from the beach, and find the Logis Manthey. It’s ideal: there’s a wall around the building and we can park the bikes on the lawn inside. The price is almost 40% less than the beachfront.

…and a visitor dropped in during the night.

Since 5 AM we’ve heard the odd truck, but there is very little traffic here. We manage a fairly early getaway after getting spotted by a goatherd who wants food for his village. How can we possibly do that?

The RN1 passes by Dolisie, so we just fill up and move on. My wife gets all the attention. It must be the red bike.

We have a particular interest in this area, as 30 South African families have been given 30 year leases on 1200 hectare farms that were abandoned by the French in the 1960’s at Malolo, 50km north of Dolisie.

It’s a government initiative to reduce their reliance on oil money to pay for imported food, and it started in 2009 when they approached Wynand du Toit (more on him later) to persuade some South African farmers to settle here to help provide food security for the country.

As in much of Africa, commercial farming is a rarity here; most peasants are subsistence farmers who grow just enough for their own needs. It’s 50 km north of Dolisie, which we pass through in the late morning.

Friends of ours were among the lucky recipients in 2011, but it’s a capital-intensive undertaking in a country with almost non-existent facilities of any kind. Without commercial funding, it’s not a viable proposition unless you have plenty of capital. Since they have neither, they have not been able to make the move.

Although we sent emails to our countrymen when we first arrived in Brazzaville, there have been no replies. And we have no phone numbers. So, sadly, we have to pass up the opportunity to drop in. Back home I investigate and it sounds like the whole exercise went sour- by 2014 only 9 farmers were still farming here. Dorsland Trekkers déjà vu?

We come across a few forlorn toll booths. There’s little truck traffic and bikes have free passage. As it should be.

There’s the odd refreshment stall that primarily caters for the passing truck trade. At least the fruit is fresh.

From Dolisie the road passes through the Dimonika Reserve before dropping steeply on the last section, and by lunchtime we start descending the spectacular route down the escarpment.

it’s fantastic riding.

We pull over at a short side road for a bite to eat. A very healthy diet we have here ;-) Buns, sardines, cheese, bananas…

...and two healthy travellers as well.

It starts drizzling as we pull away, and I nearly miss this bushmeat trader:

From a distance, I nearly mistook the pangolin scales for those of a fish. As I ask if I can take a picture, the hostile hunter yells “10 000CFA!”. It seems a bit rich for a photo, but it turns out that this is the price for his pangolin, which is suspended from one hind leg. When I tell him we’re not interested in a dead one, he pokes it in the belly, making it curl up in a defensive ball.

My mind is made up instantly and I pull out a wad of CFA notes. The hapless animal is cut down from the branch and stuffed into a shopping bag. And so we become the owners of a white-bellied pangolin and get entangled in the wildlife trade.

So what is the best option for the survival of this poor animal? If we release him too near his captor, he will be for sale again tomorrow. If we get caught with it, we might face arrest! We carry on for a few kilometres before turning off onto a dirt road towards a school. After making sure we haven’t been spotted, we take the pangolin among the trees to release him. After wriggling out of the bag, he is down a burrow before I can even get a good photo of him (her?). There’s gratitude for you!

Soon afterwards we hit the outskirts of Pointe Noire. It’s mayhem, and we are pretty tired from travelling most of the day.

We pull over to regroup and to locate the coastline, where we hope to be able to find accommodation. It looks like we have to carry straight on and the turn at the harbour. Along the way, some bizarre memorials- how could this small republic possibly have an interest in the World Wars?

We cross the rusty railway lines en route to the beach. The tracks are overgrown and only the wagons on the left look they are still in use.

And suddenly we are at the beach. It’s a sight for sore eyes. At a larny looking restaurant facing the sea the bellhop invites us over, assuring us that we can park at the entrance and the bikes will be fine while we head for the bar. The sight of the sea is worth a small celebration and we plop down.

The view may be great, but it turns out that accommodation here will cost a pretty penny. We decide to look for accommodation a short distance away from the beach, and find the Logis Manthey. It’s ideal: there’s a wall around the building and we can park the bikes on the lawn inside. The price is almost 40% less than the beachfront.

NiteOwl

Pack Dog

- Joined

- Dec 31, 2012

- Messages

- 98

- Reaction score

- 0

- Location

- Office Adventurer

- Bike

- Honda XRV 750 Africa Twin

So: where to next?

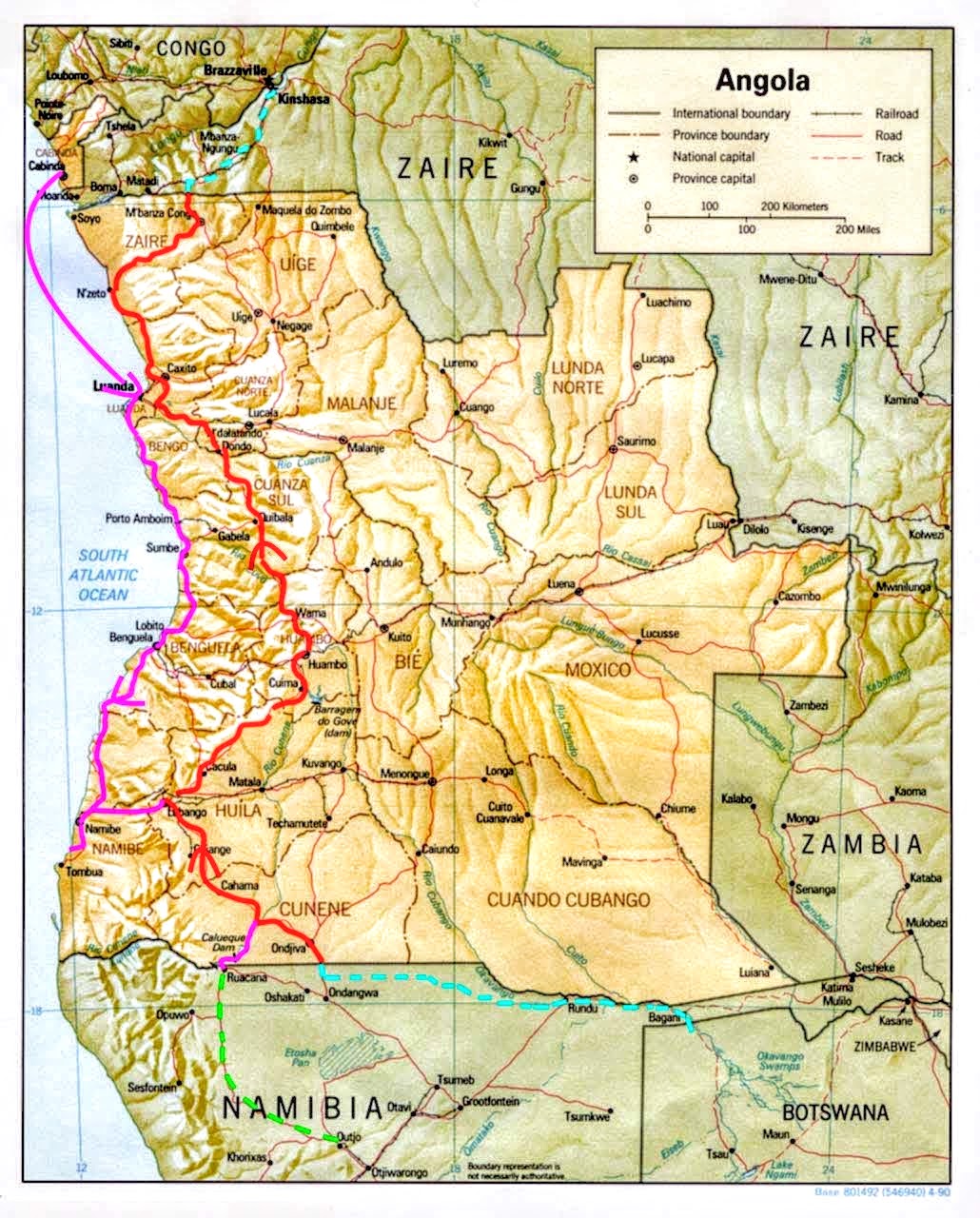

Pointe-Noire is still 150km from the northern edge of Angola, at least a day by boat from here.

Cabinda is the logical destination where our return path will be decided. The GPS says it’s 137km to the capital (also called Cabinda).

It’s a misty morning and traffic is thin on our way out of town. We spend our last CFAs to refuel the bikes before setting off for the border at Nzassi. It’s not a long drive, along a narrow road that cuts through the dense vegetation. We pass a couple of villages and lots of school kids along the way.

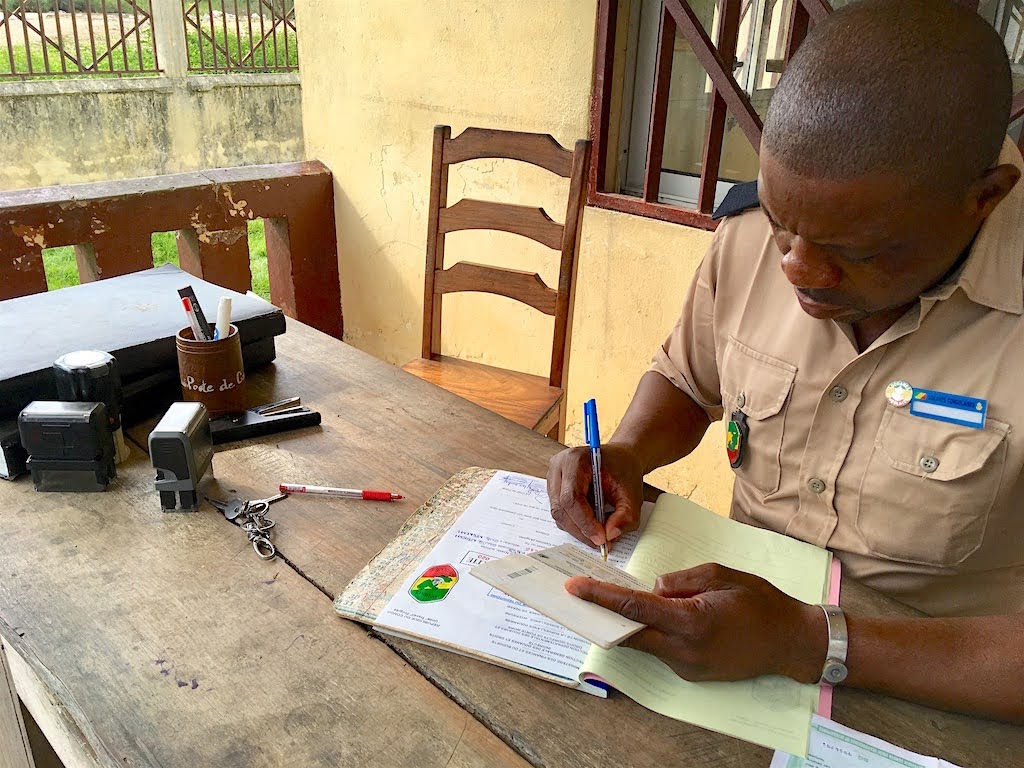

The border is a guarded boom at the end of a road lined by shops and stalls. Money changers close in as we dismount, but we have no CFAs left to exchange. They direct us to the police station, where they copy the details of our bikes in a book. Next it’s customs, who write out a release for the bikes, and finally immigration who stamp us out of the Congo.

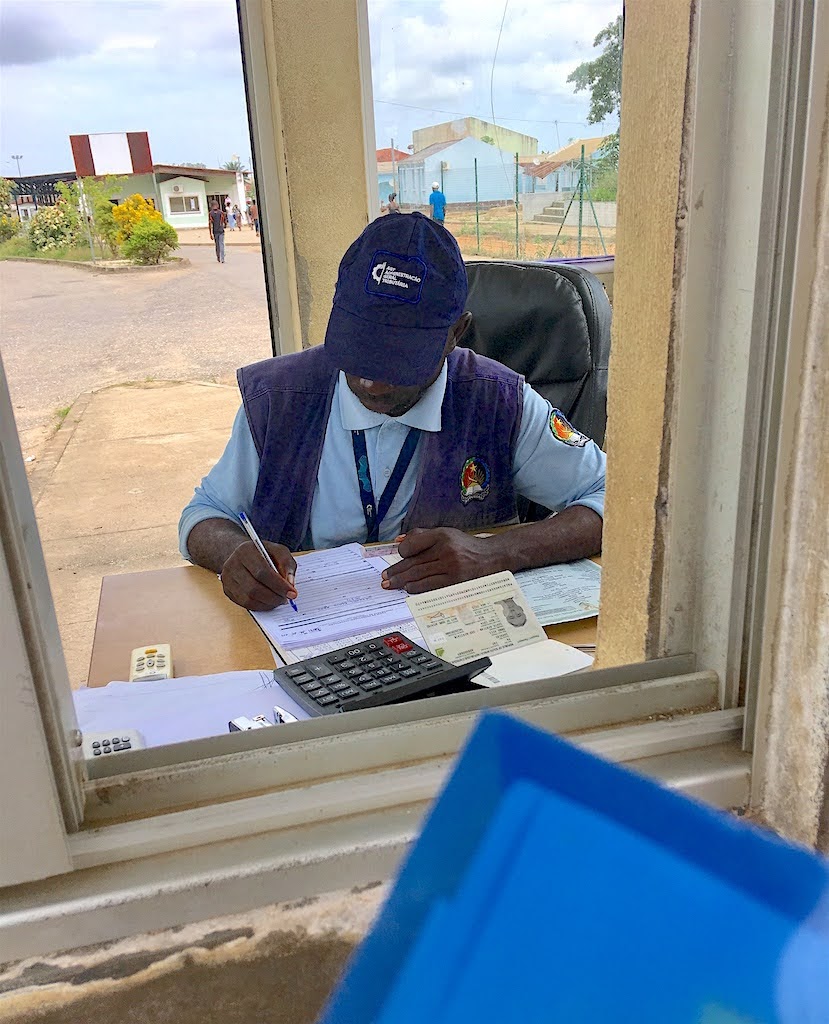

Officialdom on the Cabinda side is quite spread out and the process is rather drawn out, but it is similar to Oshikango and the officials are friendly. There’s a long passage to Immigration where passports are checked and our bikes are photographed. We again pay Customs Kz 6336 for each TIP, and after getting a police clearance we are allowed to enter the country.

Once though, there are two checkpoints manned by heavily armed soldiers where our paperwork is carefully checked. Why all the fuss? The answer if FLEC- the Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda. It’s a liberation movement with its roots in the decision by the Portuguese to incorporate the erstwhile Portuguese Congo into Angola even after the Carnation Revolution.

For Angola, the oil-rich enclave is a strategic asset that contributes 60% of their oil revenue. The natives have cottoned on that they could all be millionaires if this revenue went to them instead. With the artificial attachment between the two regions, it’s a conflict that is likely to simmer on until the oil runs out. Unsurprisingly, given the direct neighbours, the culture and language is distinctly more French than Portuguese here.

During South Africa’s involvement in the Angolan War, a recce team of nine men was dropped off from a submarine to blow up the oil tanks in Cabinda’s harbour. In order to make it look like a rebel attack, they wore Unita uniforms and were tasked to attack from inland, which required a lengthy march behind enemy lines. They were discovered the next morning and in the ensuing firefight, two men were killed, their leader was wounded and captured while the remaining six managed to escape.

That leader was captain Wynand du Toit, and he was held in solitary confinement for more than two years before being released in a POW exchange. The same man who led a group of South African farmers to Malolo in the Congo 24 years later. How the wheel turns!

After the second checkpoint, the scenery becomes rural and we stop at a large mangrove swamp to take a look at the fishermen bringing in a catch. The small fish are scooped up into plastic shopping bags and sold to passers-by.

Gradually there are more signs of human settlement as we approach the coast and pull up for lunch on a rusty pier at Landana where the waves crash around us.

As the housing changes from branches to bricks it's clear that we are approaching Cabinda city.

The first sign of city life: the national football stadium, which hosted the 2010 African Cup of Nations.

Cabinda city is considerably smaller than Pointe Noire. There are really only two roads of interest: one from the city centre to the airport and another along the coast. A flight out of here on an Antonov (as described by Kristo Käärmann - https://kaarmann.com/angola-back-in-the-ussr/) would be first prize, so we head for the airport first.

We end up at a guarded gate next to the passenger terminal. The guard says there may be a flight tomorrow, but we need to speak to his officer, who will only be available tomorrow morning.

So we will need to find accommodation for the night. There’s only one hotel that the GPS knows about, near the beach, and it’s not much at that. Diagonally across is a Roman Catholic church where we may be able to set up our tent. We ride over to ask, and after speaking to the priest we get permission to camp under the trees behind the paderia. There’s even a bucket shower and toilets around the corner where we can freshen up, and a supermarket next door.

A semicircle of statues face the church from the playa; they are even illuminated at night.

As the sun sets, the flares from the offshore oil platforms can be seen on the horizon while the local choir practices outside the church.

It’s lucky that we pitched our tent under a leafy tree, as we wake up (early) to a drizzly morning of what will prove to be an exhausting day.

By 08H00 we are back at the airport gate, but the officer is not yet available (hurry up and wait…) so we have a look at the options at the airport. There’s an evening flight to Luanda (as on most days) for Kz13 600, but it’s not for cargo. Like our bikes. Oops.

The guard is not comfortable with our bikes so close to his gate, so we wait in the airport parking lot until the officer eventually arrives. He makes it clear that there are no Antonov flights for civvies, but that we can fly to Soyo (Angola’s northernmost town) and get the bikes shipped there by boat which will arrive the next morning.

A local taxi biker is instructed to take us to the beach, which proves to be quite a little labyrinth. Six local cargo boats, called chatas, lie on the beach. Some are getting loaded, others are getting unloaded. They look pretty sturdy, but their 40hp outboards seem rather inadequate. Our guides:

We are led to the well-fed owner, Mpungi, who confirms that the bikes can be shipped to Soyo, but not passengers! So we will have to hand over our bikes to complete strangers on unseaworthy-looking boats, catch a flight of less than 100km for ourselves and hope that we will be reunited by tomorrow evening. It requires a huge leap of faith, but there does not seem any alternative. Fortunately, there is a police post on the beach and despite the language barrier, the officer in charge is sympathetic and assures us it’s all above board.

After some negotiation, we agree on sixty thousand Kwanza and hand over another ten thousand Kwanza to our guides to complete the paperwork. During the uncomfortable wait on the beach, I decide to quickly ride back to the airport to make sure that there is actually a flight to Soyo today. It’s just as well: the next flight is only in four day’s time!

But there is a flight to Luanda. So it’s back to the negotiations with the shipper. Surprisingly, Luanda is no problem but of course the fee nearly doubles. Mpungi looks affronted when I insist on a receipt, but after another hour and another thousand kwanzas we get one. He is getting agitated, because the tide is coming in. But there’s another problem: all the contact details are in Cabinda, so how are we going to find our bikes in Luanda? Grudgingly, he writes down the names of Joruny (Jeremy?) and Afonso with their mobile numbers.

We finally relent and ride the bikes to the Chata for loading and remove the luggage. At least eight volunteers emerge from the crowd and grab wheels, handlebars or footpegs to carry our precious bikes aboard.

The process looks rough, but the bikes are quite sturdy and nothing gets damaged. Will we ever see them again?

After our experience at the Kinshasa ferry, we’re not surprised when the porters start mumbling about compensation, but the ship’s mate nips it in the bud. That’s a bonus! By now it’s late afternoon and we have to get back to the airport to catch a plane, but we have no more transport. Our guides call a taxi, but Mpungi offers us a lift in his huge American SUV. As we load our bags, the taxi arrives and insists on payment for the call-out, the fixer needs some money and our guide is also expecting some compensation. It’s not unreasonable and we cough up our remaining Kwanzas.

After sweating it out on the beach for most of the day, the air-conditioned comfort of the Cadillac is a welcome relief as we get whisked to the airport. Just when it looks like everything has fallen into place, Mpungi says our dollar bills are not legal tender. The problem is that the US treasury changes their design every few years, and our bills date back to 2003. Fortunately, a passer-by overhears the conversation and swaps our $100 bill for a “fresh” one, saying he will exchange it at the bank.

The problem is that the US treasury changes their design every few years, and our bills date back to 2003. Fortunately, a passer-by overhears the conversation and swaps our $100 bill for a “fresh” one, saying he will exchange it at the bank.

Our saviour speaks good English as well, and escorts us to the ticket counter where we hit the next snag: the flight to Luanda is fully booked! But this is Africa, and in short order a tout appears from outside, saying he still has two tickets for the next flight. It’s a rip-off, but now we really need to get to Luanda rather than hang around Cabinda for another day. We draw the necessary kwanzas from the ATM in the Departure hall and head for the check-in desk.

It’s at times like these that you really appreciate a luggage solution that you can carry with all your biking gear on. The weigh-in is a farce and we get squeezed into the rearmost seats of the little Beechcraft 1900 with our belongings above, below and behind us.

It’s dark as we descend towards the capital over the fuel storage tanks near the port.

Pointe-Noire is still 150km from the northern edge of Angola, at least a day by boat from here.

Cabinda is the logical destination where our return path will be decided. The GPS says it’s 137km to the capital (also called Cabinda).

It’s a misty morning and traffic is thin on our way out of town. We spend our last CFAs to refuel the bikes before setting off for the border at Nzassi. It’s not a long drive, along a narrow road that cuts through the dense vegetation. We pass a couple of villages and lots of school kids along the way.

The border is a guarded boom at the end of a road lined by shops and stalls. Money changers close in as we dismount, but we have no CFAs left to exchange. They direct us to the police station, where they copy the details of our bikes in a book. Next it’s customs, who write out a release for the bikes, and finally immigration who stamp us out of the Congo.

Officialdom on the Cabinda side is quite spread out and the process is rather drawn out, but it is similar to Oshikango and the officials are friendly. There’s a long passage to Immigration where passports are checked and our bikes are photographed. We again pay Customs Kz 6336 for each TIP, and after getting a police clearance we are allowed to enter the country.

Once though, there are two checkpoints manned by heavily armed soldiers where our paperwork is carefully checked. Why all the fuss? The answer if FLEC- the Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda. It’s a liberation movement with its roots in the decision by the Portuguese to incorporate the erstwhile Portuguese Congo into Angola even after the Carnation Revolution.

For Angola, the oil-rich enclave is a strategic asset that contributes 60% of their oil revenue. The natives have cottoned on that they could all be millionaires if this revenue went to them instead. With the artificial attachment between the two regions, it’s a conflict that is likely to simmer on until the oil runs out. Unsurprisingly, given the direct neighbours, the culture and language is distinctly more French than Portuguese here.

During South Africa’s involvement in the Angolan War, a recce team of nine men was dropped off from a submarine to blow up the oil tanks in Cabinda’s harbour. In order to make it look like a rebel attack, they wore Unita uniforms and were tasked to attack from inland, which required a lengthy march behind enemy lines. They were discovered the next morning and in the ensuing firefight, two men were killed, their leader was wounded and captured while the remaining six managed to escape.

That leader was captain Wynand du Toit, and he was held in solitary confinement for more than two years before being released in a POW exchange. The same man who led a group of South African farmers to Malolo in the Congo 24 years later. How the wheel turns!

After the second checkpoint, the scenery becomes rural and we stop at a large mangrove swamp to take a look at the fishermen bringing in a catch. The small fish are scooped up into plastic shopping bags and sold to passers-by.

Gradually there are more signs of human settlement as we approach the coast and pull up for lunch on a rusty pier at Landana where the waves crash around us.

As the housing changes from branches to bricks it's clear that we are approaching Cabinda city.

The first sign of city life: the national football stadium, which hosted the 2010 African Cup of Nations.

Cabinda city is considerably smaller than Pointe Noire. There are really only two roads of interest: one from the city centre to the airport and another along the coast. A flight out of here on an Antonov (as described by Kristo Käärmann - https://kaarmann.com/angola-back-in-the-ussr/) would be first prize, so we head for the airport first.

We end up at a guarded gate next to the passenger terminal. The guard says there may be a flight tomorrow, but we need to speak to his officer, who will only be available tomorrow morning.

So we will need to find accommodation for the night. There’s only one hotel that the GPS knows about, near the beach, and it’s not much at that. Diagonally across is a Roman Catholic church where we may be able to set up our tent. We ride over to ask, and after speaking to the priest we get permission to camp under the trees behind the paderia. There’s even a bucket shower and toilets around the corner where we can freshen up, and a supermarket next door.

A semicircle of statues face the church from the playa; they are even illuminated at night.

As the sun sets, the flares from the offshore oil platforms can be seen on the horizon while the local choir practices outside the church.

It’s lucky that we pitched our tent under a leafy tree, as we wake up (early) to a drizzly morning of what will prove to be an exhausting day.

By 08H00 we are back at the airport gate, but the officer is not yet available (hurry up and wait…) so we have a look at the options at the airport. There’s an evening flight to Luanda (as on most days) for Kz13 600, but it’s not for cargo. Like our bikes. Oops.

The guard is not comfortable with our bikes so close to his gate, so we wait in the airport parking lot until the officer eventually arrives. He makes it clear that there are no Antonov flights for civvies, but that we can fly to Soyo (Angola’s northernmost town) and get the bikes shipped there by boat which will arrive the next morning.

A local taxi biker is instructed to take us to the beach, which proves to be quite a little labyrinth. Six local cargo boats, called chatas, lie on the beach. Some are getting loaded, others are getting unloaded. They look pretty sturdy, but their 40hp outboards seem rather inadequate. Our guides:

We are led to the well-fed owner, Mpungi, who confirms that the bikes can be shipped to Soyo, but not passengers! So we will have to hand over our bikes to complete strangers on unseaworthy-looking boats, catch a flight of less than 100km for ourselves and hope that we will be reunited by tomorrow evening. It requires a huge leap of faith, but there does not seem any alternative. Fortunately, there is a police post on the beach and despite the language barrier, the officer in charge is sympathetic and assures us it’s all above board.

After some negotiation, we agree on sixty thousand Kwanza and hand over another ten thousand Kwanza to our guides to complete the paperwork. During the uncomfortable wait on the beach, I decide to quickly ride back to the airport to make sure that there is actually a flight to Soyo today. It’s just as well: the next flight is only in four day’s time!

But there is a flight to Luanda. So it’s back to the negotiations with the shipper. Surprisingly, Luanda is no problem but of course the fee nearly doubles. Mpungi looks affronted when I insist on a receipt, but after another hour and another thousand kwanzas we get one. He is getting agitated, because the tide is coming in. But there’s another problem: all the contact details are in Cabinda, so how are we going to find our bikes in Luanda? Grudgingly, he writes down the names of Joruny (Jeremy?) and Afonso with their mobile numbers.

We finally relent and ride the bikes to the Chata for loading and remove the luggage. At least eight volunteers emerge from the crowd and grab wheels, handlebars or footpegs to carry our precious bikes aboard.

The process looks rough, but the bikes are quite sturdy and nothing gets damaged. Will we ever see them again?

After our experience at the Kinshasa ferry, we’re not surprised when the porters start mumbling about compensation, but the ship’s mate nips it in the bud. That’s a bonus! By now it’s late afternoon and we have to get back to the airport to catch a plane, but we have no more transport. Our guides call a taxi, but Mpungi offers us a lift in his huge American SUV. As we load our bags, the taxi arrives and insists on payment for the call-out, the fixer needs some money and our guide is also expecting some compensation. It’s not unreasonable and we cough up our remaining Kwanzas.

After sweating it out on the beach for most of the day, the air-conditioned comfort of the Cadillac is a welcome relief as we get whisked to the airport. Just when it looks like everything has fallen into place, Mpungi says our dollar bills are not legal tender.

Our saviour speaks good English as well, and escorts us to the ticket counter where we hit the next snag: the flight to Luanda is fully booked! But this is Africa, and in short order a tout appears from outside, saying he still has two tickets for the next flight. It’s a rip-off, but now we really need to get to Luanda rather than hang around Cabinda for another day. We draw the necessary kwanzas from the ATM in the Departure hall and head for the check-in desk.

It’s at times like these that you really appreciate a luggage solution that you can carry with all your biking gear on. The weigh-in is a farce and we get squeezed into the rearmost seats of the little Beechcraft 1900 with our belongings above, below and behind us.

It’s dark as we descend towards the capital over the fuel storage tanks near the port.

More please!!! :thumleft: :drif: :drif:

ChrisL - DUSTRIDERS said:More please!!! :thumleft: :drif: :drif:

+1 :thumleft:

Truly epic, this trip! :hello2:

Thanks for the great TR.

Not a single wheelie or burn-out on this trip ;D

Please keep it coming, I know it is a lot of prep work.

Not a single wheelie or burn-out on this trip ;D

Please keep it coming, I know it is a lot of prep work.

NiteOwl

Pack Dog

- Joined

- Dec 31, 2012

- Messages

- 98

- Reaction score

- 0

- Location

- Office Adventurer

- Bike

- Honda XRV 750 Africa Twin

We’ve given little thought to the small matter of finding accommodation in what is rumoured to be the most expensive city in the world (yeah, really) and home to some 8 million people. One option we know of is the yacht club, where one can reportedly camp for free, but trying to locate and negotiate that at night may be tricky.

Luanda’s airport is rather modest and after lugging our kit to the waiting area outside, we decide to regroup before finding a room for the night. I fetch drinks from one of the snack bars nearby, and with the little bit of airtime left on our Angolan SIMcard, we manage to locate the Soleme Guesthouse. It’s near the airport, family-owned and has a good review as well as an empty room.

Although our taxi-driver gets lost and has to do a long detour, the manageress, Maria, is very caring and quickly produces two omelettes for us. She has been to South Africa, also speaks French and a bit of English so we chat a bit before turning in for the night- it’s been a very long day and we are bushed.

The lounge and dining area:

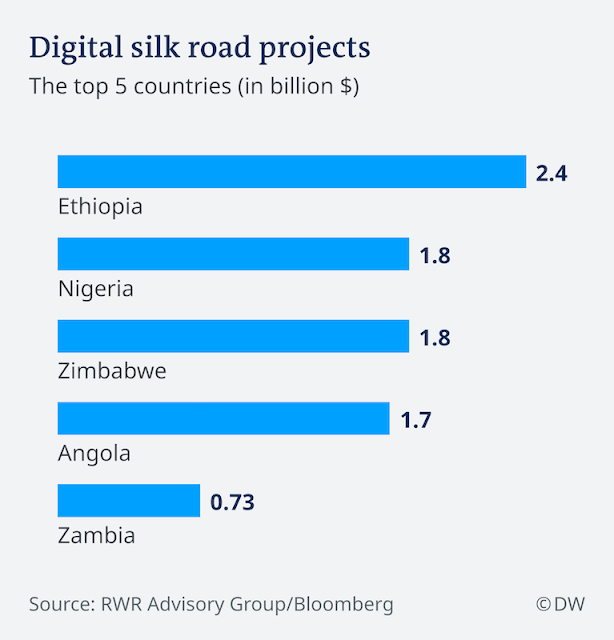

In the morning we get a better feel for the layout of our lodging. It’s actually quite central, and over breakfast we meet some of the other guests. They are here on business, and most speak English, too. The food is fresh and tasty, but the fare per night is Kz 34 000 (R 1500) and who knows how long it will take for our bikes to arrive? So we decide to wash our clothes and then look for a coffee shop, explore Luanda and hopefully check out the yacht club (where you can camp for free, remember). Before long, clear signs of Chinese infrastructure:

This is part of China’s Digital Silk Road strategy, a $200B leg of the Belt and Road initiative (Google BRI for details), China’s grand scheme to migrate from manufacturing dominance to leadership of the 4th Industrial Revolution. SADC countries feature strongly among the recipients.

Our walk starts badly, when we attempt to turn up a street with some soldiers in front of a house. There are no specific signs, but entry is verboten and we are quickly shepherded away. It takes a while to figure it out- we happen to be staying within two blocks of president João Lourenço’s pad! In fact, there is a whole compound of government buildings between our lodgings and the port. We do eventually find a decent café hidden amongst them and savour the fare.

With all this officialdom around, carrying a camera seems like a really risky idea. I leave it in our room as we navigate down to the esplanade- so unfortunately not too many pictures of Luanda other than a few cellphone shots.

We follow the beachfront along the water’s edge. The streets are very wide, and there are some impressive buildings around, paid for by all the oil that drives this economy. A huge poster of the prez adorns the military ministry: he used to be the minister of defence before getting the top job in the party and the country.

After a walk of about 5 km, we enter the yacht club and take a look around. A gaggle of young sailors are wheeling in Optimist dinghies to rinse them down before parking them along the edge of the marina opposite the bar.

There are open spaces between the buildings, but nothing that looks like ablutions or a camp site. And there is an overpowering stench of fish. Maybe it is possible to camp here, but lugging all our stuff here or locating our bikes from this place (no wifi…) compares rather poorly with our newly acquired home. We decide to stay put and rather try to negotiate a better rate.

If we’d walked a few kilometres further south and taken a little more interest in sightseeing here, we could have seen this, too (photo from Tripadvisor’s website):

It’s Agostinho Neto’s mausoleum (shipped straight from North Korea, no less) rising 120m above the cityscape. His stature here is comparable to that of Mandela back in our neck of the woods. There's a museum underneath the spire that should be quite interesting.

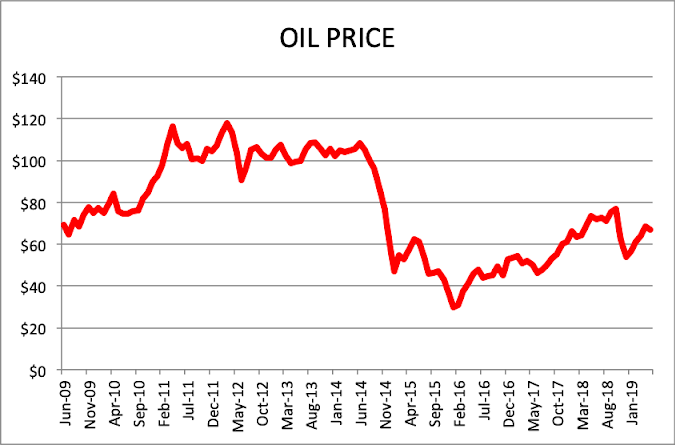

Luanda has a striking number of half-finished construction projects, their cranes breaking the skyline like giant insects. They are part of the dos Santos government’s over-reliance on oil revenues and the resulting economic crisis Lourenço inherited in 2017, three years after the oil price tanked.

Some snapshots of the Angolan capital along the way back to our rooms. Here is the eye-catching unknown soldier memorial:

Graffiti:

There are supermarkets quite similar to those of Brazzaville here, and after drawing some more kwanzas (we will soon need quite a few) we stock up on food, as supper is not normally part of the fare at the Soleme. Back at the guesthouse, we extend our stay before tucking into our new supplies.

Having explored a bit of the city, we are starting to feel more at ease in Luanda , but there’s the lingering worry of our bikes: when, if ever, will we see them again? It’s Saturday, and we tried to get hold of Jovany and Afonso since this morning- with no response. Afonso’s phone is off-line, Jovany has yet to read my message.

I decide to contact Nelson, who helped us with translation in Huambo and is presently filming a basketball tournament in Luanda. After explaining our predicament, he asks me to send him a copy of the invoice. He pronounces it “genuine” and says we should get our bikes delivered, even though it may take some time. He promises to try to get hold of our missing shipping men, but nothing comes of it.

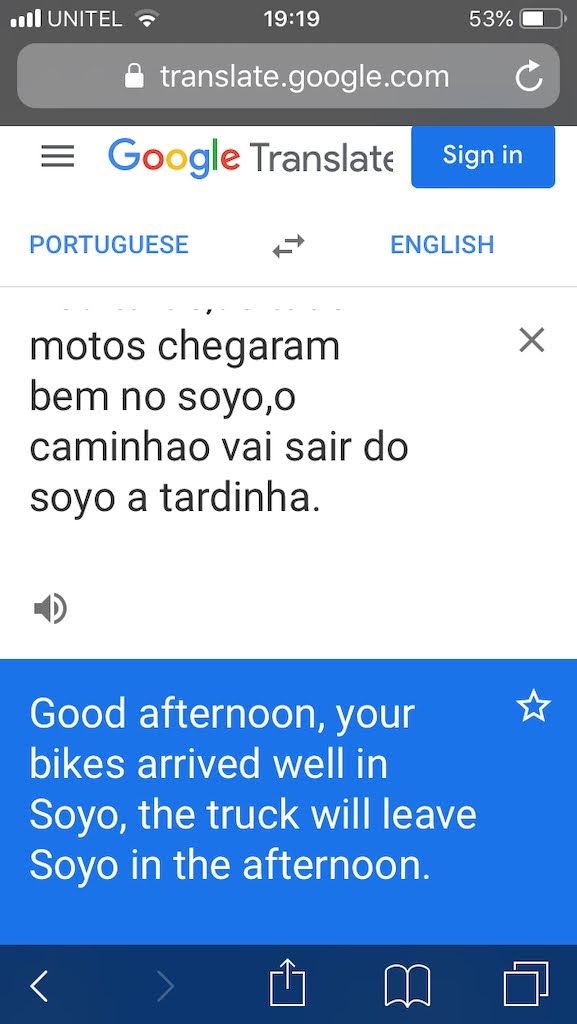

After lunch we send a message to our shipper in Cabinda, who replies late in the afternoon. Google Translate to the rescue:

Proof of life! It’s now clear that part of the transport will be by road. Luanda is some 440 km from Soyo, so it’s unlikely that the truck will be here before Monday- this is Africa after all. We spend a tense night nevertheless, as three (or more ?) nights in this place is going to be longer and more expensive than we had hoped.

At breakfast the next morning, we strike up a conversation with the ladies around the table, who are quite interested in our trip. Barbara, who sits opposite us, is originally from the Czech Republic. She works for SADC, has spent a few years working in Johannesburg and is married to a Mozambican lawyer. So apart from English, she can speak Portuguese as well, and is prepared to assist us. She proves to be a godsend.

Barbara gives a sobering view of the difference between South Africa and the rest of the SADC countries. Despite the poor infrastructure here, it’s easier to get things done (in Angola) than in South Africa. People in Angola are less self-absorbed and more sharing. Whereas South Africa is structured to keep rich and poor areas apart, it’s the opposite here. That is reflected in the gini coefficient, which is much lower here than in South Africa. Part of this is because Angola has a very young population, due to the high birthrate: the median age here is under 17 years, SA’s is nearly 28.

After breakfast, the first step is to go and buy airtime, as some phone calls will be required. Back at the Soleme, we join Barbara for coffee. She is calm, focussed and persuasive as she calls Jovany, who has been waiting for us to call(!) but can’t tell us anything about the whereabouts of the cargo. That turns out to be Afonso’s domain, who says our bikes will arrive shortly, but he can’t say where. Barbara insists on specifics and he promises to call back in an hour. We eventually learn that the dropoff will be at the military air cargo terminal near the airport, in 1 or 2 hour’s time.

There's no point in hanging around now- we pack up, get dressed and settle our bill. Then a pleasant and unusual surprise: the bill is less than advertised and with a free ride to the airport to boot! Barbara offers to come along and gets directions from Afonso en route. Luanda’s notorious traffic is a breeze, as it’s a Sunday.

We end up at a military warehouse on the edge of Luanda’s airport, where Barbara convinces the guard to let us wait inside while she returns to the hotel with the driver and our profuse thanks. Afonso arrives less than 30 minutes later, saying the bikes are being offloaded across the road! My wife jogs across the road and soon roars into the parking lot, grinning from ear to ear. What a relief!

My bike is standing on the pavement behind a large truck opposite the military terminal when I get across the road. There’s no damage to the bikes other than some bent mirrors, and nothing is missing- not even our water bottles or fuel containers. My distrust of the shipper was clearly misplaced, he has delivered as promised. A humbling experience. Welcome to Angola!

Luanda’s airport is rather modest and after lugging our kit to the waiting area outside, we decide to regroup before finding a room for the night. I fetch drinks from one of the snack bars nearby, and with the little bit of airtime left on our Angolan SIMcard, we manage to locate the Soleme Guesthouse. It’s near the airport, family-owned and has a good review as well as an empty room.

Although our taxi-driver gets lost and has to do a long detour, the manageress, Maria, is very caring and quickly produces two omelettes for us. She has been to South Africa, also speaks French and a bit of English so we chat a bit before turning in for the night- it’s been a very long day and we are bushed.

The lounge and dining area:

In the morning we get a better feel for the layout of our lodging. It’s actually quite central, and over breakfast we meet some of the other guests. They are here on business, and most speak English, too. The food is fresh and tasty, but the fare per night is Kz 34 000 (R 1500) and who knows how long it will take for our bikes to arrive? So we decide to wash our clothes and then look for a coffee shop, explore Luanda and hopefully check out the yacht club (where you can camp for free, remember). Before long, clear signs of Chinese infrastructure:

This is part of China’s Digital Silk Road strategy, a $200B leg of the Belt and Road initiative (Google BRI for details), China’s grand scheme to migrate from manufacturing dominance to leadership of the 4th Industrial Revolution. SADC countries feature strongly among the recipients.

Our walk starts badly, when we attempt to turn up a street with some soldiers in front of a house. There are no specific signs, but entry is verboten and we are quickly shepherded away. It takes a while to figure it out- we happen to be staying within two blocks of president João Lourenço’s pad! In fact, there is a whole compound of government buildings between our lodgings and the port. We do eventually find a decent café hidden amongst them and savour the fare.

With all this officialdom around, carrying a camera seems like a really risky idea. I leave it in our room as we navigate down to the esplanade- so unfortunately not too many pictures of Luanda other than a few cellphone shots.

We follow the beachfront along the water’s edge. The streets are very wide, and there are some impressive buildings around, paid for by all the oil that drives this economy. A huge poster of the prez adorns the military ministry: he used to be the minister of defence before getting the top job in the party and the country.

After a walk of about 5 km, we enter the yacht club and take a look around. A gaggle of young sailors are wheeling in Optimist dinghies to rinse them down before parking them along the edge of the marina opposite the bar.

There are open spaces between the buildings, but nothing that looks like ablutions or a camp site. And there is an overpowering stench of fish. Maybe it is possible to camp here, but lugging all our stuff here or locating our bikes from this place (no wifi…) compares rather poorly with our newly acquired home. We decide to stay put and rather try to negotiate a better rate.

If we’d walked a few kilometres further south and taken a little more interest in sightseeing here, we could have seen this, too (photo from Tripadvisor’s website):

It’s Agostinho Neto’s mausoleum (shipped straight from North Korea, no less) rising 120m above the cityscape. His stature here is comparable to that of Mandela back in our neck of the woods. There's a museum underneath the spire that should be quite interesting.

Luanda has a striking number of half-finished construction projects, their cranes breaking the skyline like giant insects. They are part of the dos Santos government’s over-reliance on oil revenues and the resulting economic crisis Lourenço inherited in 2017, three years after the oil price tanked.

Some snapshots of the Angolan capital along the way back to our rooms. Here is the eye-catching unknown soldier memorial:

Graffiti:

There are supermarkets quite similar to those of Brazzaville here, and after drawing some more kwanzas (we will soon need quite a few) we stock up on food, as supper is not normally part of the fare at the Soleme. Back at the guesthouse, we extend our stay before tucking into our new supplies.

Having explored a bit of the city, we are starting to feel more at ease in Luanda , but there’s the lingering worry of our bikes: when, if ever, will we see them again? It’s Saturday, and we tried to get hold of Jovany and Afonso since this morning- with no response. Afonso’s phone is off-line, Jovany has yet to read my message.

I decide to contact Nelson, who helped us with translation in Huambo and is presently filming a basketball tournament in Luanda. After explaining our predicament, he asks me to send him a copy of the invoice. He pronounces it “genuine” and says we should get our bikes delivered, even though it may take some time. He promises to try to get hold of our missing shipping men, but nothing comes of it.

After lunch we send a message to our shipper in Cabinda, who replies late in the afternoon. Google Translate to the rescue:

Proof of life! It’s now clear that part of the transport will be by road. Luanda is some 440 km from Soyo, so it’s unlikely that the truck will be here before Monday- this is Africa after all. We spend a tense night nevertheless, as three (or more ?) nights in this place is going to be longer and more expensive than we had hoped.

At breakfast the next morning, we strike up a conversation with the ladies around the table, who are quite interested in our trip. Barbara, who sits opposite us, is originally from the Czech Republic. She works for SADC, has spent a few years working in Johannesburg and is married to a Mozambican lawyer. So apart from English, she can speak Portuguese as well, and is prepared to assist us. She proves to be a godsend.

Barbara gives a sobering view of the difference between South Africa and the rest of the SADC countries. Despite the poor infrastructure here, it’s easier to get things done (in Angola) than in South Africa. People in Angola are less self-absorbed and more sharing. Whereas South Africa is structured to keep rich and poor areas apart, it’s the opposite here. That is reflected in the gini coefficient, which is much lower here than in South Africa. Part of this is because Angola has a very young population, due to the high birthrate: the median age here is under 17 years, SA’s is nearly 28.

After breakfast, the first step is to go and buy airtime, as some phone calls will be required. Back at the Soleme, we join Barbara for coffee. She is calm, focussed and persuasive as she calls Jovany, who has been waiting for us to call(!) but can’t tell us anything about the whereabouts of the cargo. That turns out to be Afonso’s domain, who says our bikes will arrive shortly, but he can’t say where. Barbara insists on specifics and he promises to call back in an hour. We eventually learn that the dropoff will be at the military air cargo terminal near the airport, in 1 or 2 hour’s time.

There's no point in hanging around now- we pack up, get dressed and settle our bill. Then a pleasant and unusual surprise: the bill is less than advertised and with a free ride to the airport to boot! Barbara offers to come along and gets directions from Afonso en route. Luanda’s notorious traffic is a breeze, as it’s a Sunday.

We end up at a military warehouse on the edge of Luanda’s airport, where Barbara convinces the guard to let us wait inside while she returns to the hotel with the driver and our profuse thanks. Afonso arrives less than 30 minutes later, saying the bikes are being offloaded across the road! My wife jogs across the road and soon roars into the parking lot, grinning from ear to ear. What a relief!

My bike is standing on the pavement behind a large truck opposite the military terminal when I get across the road. There’s no damage to the bikes other than some bent mirrors, and nothing is missing- not even our water bottles or fuel containers. My distrust of the shipper was clearly misplaced, he has delivered as promised. A humbling experience. Welcome to Angola!

AfriqueDS

Race Dog

faaaantastic report - one of the best

Finally finished reading this from the start today what an adventure, you must have abnormal patience to handle the africa factor, well done for saving the pangolin, and please get home now !!

Sent from my SM-N970F using Tapatalk

Sent from my SM-N970F using Tapatalk

NiteOwl

Pack Dog

- Joined

- Dec 31, 2012

- Messages

- 98

- Reaction score

- 0

- Location

- Office Adventurer

- Bike

- Honda XRV 750 Africa Twin

It does not take long to strap our luggage back where it belongs, get our bearings and head for the coast. We chatter through the traffic about our good fortune to have met Barbara and getting our bikes back again. Both Tornados still run like clockwork and it’s great to be moving once more- we still have 4000km to go.

As we are to learn quite soon, the views along the Angolan coastline are a revelation. Each time you crest a rise, a completely different landscape unfolds in front of your eyes- the best riding of the trip. Mussulo Island (actually a peninsula) is the first distant vista to catch the eye:

For some reason the GPS is insistent that we should hold left, towards Dondo, while we really want to follow the coast southwards (all will be revealed).

Half an hour later, the stately baobabs on the edge of the Quiçama (Kissama) National Park make us pull over for some photos.

It’s Angola’s only functional park and covers 3 million acres. The civil war decimated the large mammals that used to roam these plains, in particular the giant sable antelope (only 8 survived). Although restocking efforts (similar Gorongosa in Mozambique) are underway, it will probably take decades to re-establish the fauna here as the country has more urgent priorities.

Across the road, the salt works of Salinas de Flamingo glisten in the sun.

Only a few kilometres further, this colourful erosion, marked as "Lunar Landscape" on T4A. There’s a lookout point and a 4x4 route from the main road down to the beach as well.

At Barra do Cuanza we top up our remaining fuel from Cabinda, before crossing this cable-stayed bridge across the mouth of the Cuanza river.

It’s an impressive construction, 400m across, and saved from collapse in 2013 just before the oil price collapsed. Many bridges were damaged during the war, hampering economic recovery even now. Since most of Angola’s large rivers are too deep to cross by vehicle, ferries are the only option until repairs or (in most cases) reconstruction, are completed.

The coastal road is the EN100, and although it’s a modest single road (like our regional roads), it’s in pretty good condition and we make steady progress.

Traffic is surprisingly light, with occasional pockets of vehicles. No scooters or motorcycles here, except for a BMW tour group we passed late in the afternoon.

There’s the odd detour where repairs are in progress. Not really a problem in this region, where dust is more common than mud.

The rest of the afternoon passes all too quickly as we swerve inland before the coastline reappears over the horizon. Rolling hills:

It’s dusk by the time we reach Porto Amboim. Its port served to export the coffee produced at Gabela, 70km inland from here. Now, it looks more like a small fishing port.

The main road runs right through the small town, but after our luxury stay in Luanda, it’s time to look for a camping spot. There’s a Puma service station on the outskirts of the town where we refuel and buy supplies for supper. My steering feels heavy as we pull away, and slowly gets worse- another puncture! Although the front tyre is deflating, the sidewalls prevent it from collapsing.

It takes us 4 km to find a side road with no sign of habitation. After pitching the tent, I set to work on the tyre while mrs Owl gets to work making supper. And the mozzies make a meal of us both. We must be near a swamp!

As we are to learn quite soon, the views along the Angolan coastline are a revelation. Each time you crest a rise, a completely different landscape unfolds in front of your eyes- the best riding of the trip. Mussulo Island (actually a peninsula) is the first distant vista to catch the eye:

For some reason the GPS is insistent that we should hold left, towards Dondo, while we really want to follow the coast southwards (all will be revealed).

Half an hour later, the stately baobabs on the edge of the Quiçama (Kissama) National Park make us pull over for some photos.

It’s Angola’s only functional park and covers 3 million acres. The civil war decimated the large mammals that used to roam these plains, in particular the giant sable antelope (only 8 survived). Although restocking efforts (similar Gorongosa in Mozambique) are underway, it will probably take decades to re-establish the fauna here as the country has more urgent priorities.

Across the road, the salt works of Salinas de Flamingo glisten in the sun.

Only a few kilometres further, this colourful erosion, marked as "Lunar Landscape" on T4A. There’s a lookout point and a 4x4 route from the main road down to the beach as well.

At Barra do Cuanza we top up our remaining fuel from Cabinda, before crossing this cable-stayed bridge across the mouth of the Cuanza river.

It’s an impressive construction, 400m across, and saved from collapse in 2013 just before the oil price collapsed. Many bridges were damaged during the war, hampering economic recovery even now. Since most of Angola’s large rivers are too deep to cross by vehicle, ferries are the only option until repairs or (in most cases) reconstruction, are completed.

The coastal road is the EN100, and although it’s a modest single road (like our regional roads), it’s in pretty good condition and we make steady progress.

Traffic is surprisingly light, with occasional pockets of vehicles. No scooters or motorcycles here, except for a BMW tour group we passed late in the afternoon.

There’s the odd detour where repairs are in progress. Not really a problem in this region, where dust is more common than mud.

The rest of the afternoon passes all too quickly as we swerve inland before the coastline reappears over the horizon. Rolling hills:

It’s dusk by the time we reach Porto Amboim. Its port served to export the coffee produced at Gabela, 70km inland from here. Now, it looks more like a small fishing port.

The main road runs right through the small town, but after our luxury stay in Luanda, it’s time to look for a camping spot. There’s a Puma service station on the outskirts of the town where we refuel and buy supplies for supper. My steering feels heavy as we pull away, and slowly gets worse- another puncture! Although the front tyre is deflating, the sidewalls prevent it from collapsing.

It takes us 4 km to find a side road with no sign of habitation. After pitching the tent, I set to work on the tyre while mrs Owl gets to work making supper. And the mozzies make a meal of us both. We must be near a swamp!

NiteOwl

Pack Dog

- Joined

- Dec 31, 2012

- Messages

- 98

- Reaction score

- 0

- Location

- Office Adventurer

- Bike

- Honda XRV 750 Africa Twin

It’s an uncomfortable and sticky night as we fight a running battle until our insect spray runs out. By daybreak the tent floor is littered with our tormentors who paid the ultimate price.

We are indeed at the edge of some marshy bog and have a hurried breakfast for an early departure.

We cross another bridge over a large river: the Queve/ Cueve/ Keve, whose tributaries contributed to last night’s discomfort. There are huts on either side of the river, and here’s how you get across from the one side to the other over that inky water.

As the road rises, the river’s floodplain glistens in the early morning sun.

The rest of the day feels like a National Geographic movie, with a new view after every rise.

The name of Sumbe (Novo Redondo, Ngunza Cabolo) is derived from the local Kimbundu language, meaning “to trade”. The houses on the outskirts are built on a steep sandy slope.

Once down onto level ground along the dusty detours, we come across the local supermarket and it’s a Shoprite! Every major town in Angola has a one, but most locals don’t seem able to afford what’s on the shelves.

Outside the town: more water, carving through a dolomite canyon (the Cubal river gorge).

Angola has a fault line running diagonally across it. In the northeast this line is rich in gem-grade diamonds, but here in the southwest it mainly holds minerals suitable for cement and fertiliser. Only a few km inland from Sumbe are the Sassa caves, which we unfortunately missed.

With all that water around, it’s not surprising when we run into waterbirds, like this black-headed heron:

Most of the road is in brand new condition, with the markings not yet done and the culverts still being finished by local workers- despite the Chinese sign.

Culverts are one thing, but these half- bridges could pose a nasty surprise at night. There must have been a serious communication gap at some point in the project.

Although the coastal route crosses many big rivers, their contents originate in the highlands to the east- the landscape here is actually semi-desert. If you like Namibia, you will love Angola.

The road swings back to the sea at Lobito, which unfolds in front of us as we crest the surrounding hills.

There’s another Shoprite and we make lunch under the trees in the parking lot.

It’s a dirty place, with shacks and villas standing cheek by jowl overlooking the lagoon, where people are (making a) living between makeshift salt pans.

That changes abruptly where the road crosses the Catumbela river via a striking fan style cable stay bridge that looks strangely out of place.

Benguela, the terminus for the Benguela Railway, is only 30km from Lobito. It has a completely different character, looking rather modern and clean in comparison to Lobito. It’s hard to reconcile this image with the port that served as the gateway for the slave trade to Brazil.

South of Benguela are more salt works, similar to those near Luanda. Efforts to expand them so that the country can be self-sufficient in its salt requirements have stalled due to lack of investment.

We reach Dombe Grande, an agricultural town with a palm tree-lined boulevard that has seen better days. The mill here used to produce rum from the locally grown cane juice, but that industry hit the skids when alcohol was banned in 1911. Attempts to switch production to sugar were unsuccessful, probably because the machinery was unsuitable.

Then we get to this sign, for which no dictionary is needed.

And indeed, 500m on, the tar road ends with an unfinished bridge neatly lined up to connect to it. Despite the construction starting in 2010, the project did not get completed before the money ran out.

There’s a reason for those bridges though- the road through Dombe Grande Pass is quite steep. It’s also quite bumpy, and soon one of our water bottles slips out of the cargo net and splits when it hits the ground. That may become a problem as this area is deserted; we only passed one Land Cruiser here.

At Dombe Grande town there was sign that said that the next fuel is 200km further. It looks like that may be in the village of Lucira, which we cannot reach before nightfall and there are no villages in between. By dusk we pass a cell-phone tower where the two guards confirm that there’s fuel about 80 km from here.

We ride on for another fifteen minutes, and then make a camp between the bushes just off the 4x4 track to Santa Maria (Binga Bay). The sky is crystal clear.

The soft sand makes for a good night’s rest, but by breakfast time the entire area is enveloped in a thick coastal fog and everything is damp.

The fog is so dense, that my glasses are coated in condensation. It’s worse than riding in rain!

Gradually, the mist clears as the sun’s rays penetrate.

After a while, signs of roadwork appear, and we ride up the newly compacted road deck next to the old track. Although there are wide mounds across it every kilometre or so, they’re easy to cross on the bikes, while we enjoy the scenery.

We almost make the mistake of turning towards Lucira when we spot a Puma filling station ahead. It’s indeed 200km from the sign outside Benguela, and a brand new tar road welcomes us all way to Namibe, another 200km to the south.

We are indeed at the edge of some marshy bog and have a hurried breakfast for an early departure.

We cross another bridge over a large river: the Queve/ Cueve/ Keve, whose tributaries contributed to last night’s discomfort. There are huts on either side of the river, and here’s how you get across from the one side to the other over that inky water.

As the road rises, the river’s floodplain glistens in the early morning sun.

The rest of the day feels like a National Geographic movie, with a new view after every rise.

The name of Sumbe (Novo Redondo, Ngunza Cabolo) is derived from the local Kimbundu language, meaning “to trade”. The houses on the outskirts are built on a steep sandy slope.

Once down onto level ground along the dusty detours, we come across the local supermarket and it’s a Shoprite! Every major town in Angola has a one, but most locals don’t seem able to afford what’s on the shelves.

Outside the town: more water, carving through a dolomite canyon (the Cubal river gorge).

Angola has a fault line running diagonally across it. In the northeast this line is rich in gem-grade diamonds, but here in the southwest it mainly holds minerals suitable for cement and fertiliser. Only a few km inland from Sumbe are the Sassa caves, which we unfortunately missed.

With all that water around, it’s not surprising when we run into waterbirds, like this black-headed heron:

Most of the road is in brand new condition, with the markings not yet done and the culverts still being finished by local workers- despite the Chinese sign.

Culverts are one thing, but these half- bridges could pose a nasty surprise at night. There must have been a serious communication gap at some point in the project.

Although the coastal route crosses many big rivers, their contents originate in the highlands to the east- the landscape here is actually semi-desert. If you like Namibia, you will love Angola.

The road swings back to the sea at Lobito, which unfolds in front of us as we crest the surrounding hills.

There’s another Shoprite and we make lunch under the trees in the parking lot.

It’s a dirty place, with shacks and villas standing cheek by jowl overlooking the lagoon, where people are (making a) living between makeshift salt pans.

That changes abruptly where the road crosses the Catumbela river via a striking fan style cable stay bridge that looks strangely out of place.

Benguela, the terminus for the Benguela Railway, is only 30km from Lobito. It has a completely different character, looking rather modern and clean in comparison to Lobito. It’s hard to reconcile this image with the port that served as the gateway for the slave trade to Brazil.

South of Benguela are more salt works, similar to those near Luanda. Efforts to expand them so that the country can be self-sufficient in its salt requirements have stalled due to lack of investment.

We reach Dombe Grande, an agricultural town with a palm tree-lined boulevard that has seen better days. The mill here used to produce rum from the locally grown cane juice, but that industry hit the skids when alcohol was banned in 1911. Attempts to switch production to sugar were unsuccessful, probably because the machinery was unsuitable.

Then we get to this sign, for which no dictionary is needed.

And indeed, 500m on, the tar road ends with an unfinished bridge neatly lined up to connect to it. Despite the construction starting in 2010, the project did not get completed before the money ran out.

There’s a reason for those bridges though- the road through Dombe Grande Pass is quite steep. It’s also quite bumpy, and soon one of our water bottles slips out of the cargo net and splits when it hits the ground. That may become a problem as this area is deserted; we only passed one Land Cruiser here.

At Dombe Grande town there was sign that said that the next fuel is 200km further. It looks like that may be in the village of Lucira, which we cannot reach before nightfall and there are no villages in between. By dusk we pass a cell-phone tower where the two guards confirm that there’s fuel about 80 km from here.

We ride on for another fifteen minutes, and then make a camp between the bushes just off the 4x4 track to Santa Maria (Binga Bay). The sky is crystal clear.

The soft sand makes for a good night’s rest, but by breakfast time the entire area is enveloped in a thick coastal fog and everything is damp.

The fog is so dense, that my glasses are coated in condensation. It’s worse than riding in rain!

Gradually, the mist clears as the sun’s rays penetrate.

After a while, signs of roadwork appear, and we ride up the newly compacted road deck next to the old track. Although there are wide mounds across it every kilometre or so, they’re easy to cross on the bikes, while we enjoy the scenery.

We almost make the mistake of turning towards Lucira when we spot a Puma filling station ahead. It’s indeed 200km from the sign outside Benguela, and a brand new tar road welcomes us all way to Namibe, another 200km to the south.

Kaboef said:Magic, magic. O0

Yes :thumleft:

JACOVV

Race Dog

- Joined

- Aug 9, 2009

- Messages

- 4,630

- Reaction score

- 99

- Location

- East of London EC

- Bike

- BMW R1200GS Adventure

What a RR. :deal:

Thanks.

Thanks.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 2

- Views

- 929