So we need Photostats of IDs, driver’s licences, vehicle registrations, photos of ourselves and the bikes plus a copy of the immigration stamp deposited by the sloth up the road in our passports a few minutes ago- tricky one, that. No doubt there will be a copying centre back in Oshikango doing good business from all this, and it does not take long to find one. But it is now after six, so it’s closed.

We backtrack to look for lodging, but everyone wants cash and we have spent most of ours at the last refuelling stop. After a few circuits up and down the main (only) road, we find Pisca’s Hotel. It’s only 500m from the border, with a bar as the main entrance, but behind it is a courtyard (complete with armed guard) with secure parking and a chicken coup. It’s run by a mrs Rochas -who looks seriously undernourished- but she has a soft spot for bikers (her son’s F650 is parked near the chickens), so we get a discount. And free use of her PC and printer! To top it all, she accepts credit cards.

We manage to change our credit card settings using Pisca’s wifi and draw money at the ATM nearby, so we that can (hopefully) pay for Angola’s road tax, as it is not possible to buy Kwanzas at South African Banks.

Speaking (writing?) of South Africa- we are now 2 400 km away from home. About 1 ½ times the distance from Pretoria to Cape Town.

After breakfast we find a queue of cars outside as we head for the border again. Since we’re done with Immigration already, we ride through to Customs again, and get spotted by last night’s runners before we can park the bikes in front of a hangar nearby. (Sorry, no pics- it’s a sensitive area here)

The same customs man is on duty again, and despite the fact that all the paperwork is not quite up to scratch, he performs the necessary edits, hands me two small strips of paper with a number on each and instructs a truck driver to show me where the bank is, so we can pay our Road Tax of 6336 Kwanzas (R285) per bike.

Unfortunately, this has to be paid in the local currency.

Fortunately, I spot a credit card machine on the bank official’s desk.

Unfortunately, it’s out of order and he apologises.

Fortunately, there are lots of money-changers hanging about and he calls one over. Four hundred and forty Namibian dollars buys 13 000 sweaty Kwanzas and the use of Angola’s roads for the next 90 days, or until we exit the country. Two receipts with the magic numbers are printed out in the adjacent customs office to seal the deal and we are sent back to the customs guys manning the boom.

They apologise, but now the bikes need to be inspected to check the chassis numbers against the registration papers and we have to unpack our bags to show what we are carrying into the country, especially… money. We are carrying Euros for our end destination, and dollars for emergencies (everybody seems to like the greenback!) but they are satisfied with the explanation and there is not even a suggestion of a “gift”. The official takes a picture as we leave, promising to send it to his colleague in Luvo, where we will exit Angola.

The boom lifts and we are waved off, not sure what to expect next as we enter Angola.

Angola.

It's hard to dissociate the name of the country from the 27-year civil war in which South Africa played a significant part. How did it start and how did we get involved?

When the Carnation Revolution displaced the established order in Portugal, it spelt the end of the Portuguese colonial empire. When a date was set for Angola’s independence at 11 November 1975, it set off an intense conflict for the control of the country that was to last until the death of Jonas Savimbi in 2002.

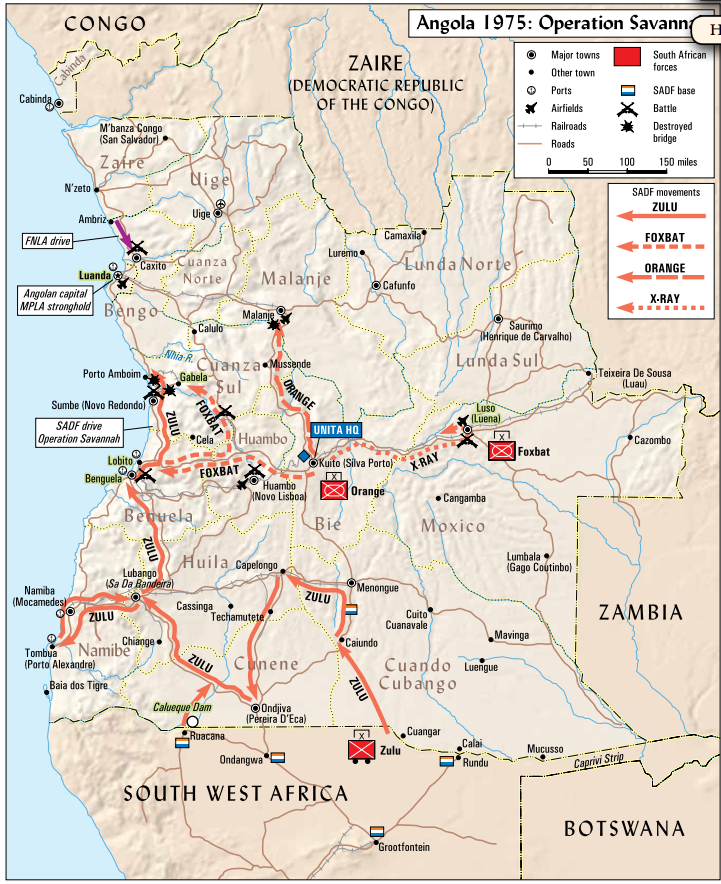

Prior to 1975, three Angolan liberation movements had tried to wrest control of the country from their colonial masters. With the withdrawal of their common enemy, they soon turned against each other and the civil war that followed became a proxy war between the Cold War protagonists. The USSR wanted the MPLA in control in Luanda, while the USA supported the FNLA in the north and UNITA in the south of the country.

South Africa’s apartheid government wanted to prevent the establishment of communist neighbours (

die Rooi Gevaar) on its northern borders, from where incursions into Namibia were conducted by the Namibian liberation movements (mainly SWAPO-

die Swart Gevaar). In response, the South African Defence Force conducted increasingly aggressive cross-border raids on SWAPO bases deep into Angola and Zambia.

By the middle of 1975, the MPLA (with Soviet support) had dished out a series of crippling defeats to both the FNLA and UNITA and it became obvious that Angola would come under communist rule by the November deadline unless something drastic happened to the balance of power. South Africa’s response, with US (CIA!) encouragement, was Operation Savannah and so the guerrilla conflict escalated into conventional warfare and Cuba entered the fray. Although SADF troops got as far north as Porto Amboim, it was too late to prevent the MPLA from being endorsed by the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) and early in 1976 the SADF withdrew back to their Caprivi bases.

South Africa continued to support UNITA as part of a strategy to counter SWAPO, while the MPLA tried to wrest control of the southern part of the country. The ensuing arms race cost Angola about 50% and South Africa some 16% of its GDP by the time a settlement was eventually reached in 1989 and Namibia gained independence. As a result, both Angola’s and South Africa’s economic development were severely curbed (by comparison, only 1% of South Africa’s GDP is spent on defence today- 2019).

While most of my generation were called up

vir volk en vaderland in the eighties, the majority of the current economically active population of Angola were not even born at the time. We’re from different eras; Life has moved on.

Back to the present: since 2017, Angola has had a new president and, unlike his South African counterpart, he is actually making a difference. Tourism is now encouraged (South Africans don’t need a visa to enter the country anymore), the officials are courteous and helpful and in the towns and cities people are sweeping the streets. It’s a menial job, but it makes a subtle difference in one’s perception that becomes stark when you reach the Congos. Bribery and corruption are no longer tolerated and, to prove the point, ex-president Dos Santos’ son has been incarcerated for fraud related to Angola’s equivalent of our Public Investment Corporation and his daughter (Africa’s richest woman!) is in exile.

Actually, little of this matters today as we enter the country. What does matter is that the local time zone is one hour behind CAT (we’ve gained an hour) and we have to adjust driving on the right (wrong??) side of the road. And now we need money and fuel.

The queue at the filling station not surprising - fuel here is half the SA price. As we have enough (hopefully!) to get to the next town, I get Kwanzas at the local ATM while my wife is garnering a fan club. Women don’t seem to drive anything around these parts, let alone a motorbike.

Something has subtly changed on both bikes and from here onwards the fuel consumption improves towards the levels I had hoped for. We comfortably make it to Ondjiva (40 km from the border) where the queue is short and the bikes get filled almost immediately. Something typical of all Angolan filling stations: the Armed (to the teeth) Guard. It’s the result of the fact that all fuel transactions (and there are many) are cash-based. So robbery must be very tempting in a country where most citizens are quite poor and AK-47s are a dime a dozen.

Apart from the generally clean impression of Ondjiva, the multitude of motorcycles versus the paucity of motorcars is striking. The road looks newly tarred and is as smooth as you could wish for- GS country! ;-)

Just outside Ondjiva we come across the first war relics- armoured combat vehicles and personnel carriers that seem to have been immobilised by artillery. These look like a couple of Soviet BRDM-2s, stranded on either side of the road, with a BTR-152 APC between them.

A bit further on there is a war memorial paying tribute to the fallen soldiers who defended the town of Mongua nearby. An abandoned T54 tank stands sentinel nearby with a broken track, its gun barrel pointing aimlessly over the passing traffic.

We stop a few kilometres further for coffee and some of the Maria biscuits we bought when we refuelled. It’s getting hot, but there’s shade along the side of the road opposite a small village from which some curious kids emerge to check us out. We share the remainder of the biscuits with them, and they are well received- we saw lots of kids in Angola, but no fat ones.

We get overtaken by some older kids on unusually-new looking bicycles. Judging by the branding, some early indoctrination by the ruling party.

Around us we see quite a lot of water puddles where cattle drink and kids play. We are approaching a river.

One hundred kilometres from Ondjiva the EN 105 road crosses the Cunene river at Xangongo. Although the water level is low, it’s clearly a huge river, with a bridge to match.

Something else about Angola- there are lots of road markers, river identifiers and signs indicating the destination, distances and road numbers and they generally look quite new. What’s less obvious is what is not there- bullet holes. I don’t think this is accidental, but part of a strategy to cover the scars of the civil war and move on. In the towns, most buildings have been patched up as well. It makes a lot of sense.

A few minutes later we pass a freedom memorial with a quote by Fidel Castro; the paint is as faded as the message, the structure and

uhuru chains are rusted, the plaster is patchy and overgrown with weeds. A footnote in history.

The scenery changes; the Mopani bushes and palm trees give way to succulents as the landscape turns more arid and the soil more sandy as we approach Cahama….

… where we refuel. This time, we’re in more of an extended village than a town and there is no Sonangol sign in sight. Instead, we find a queue of bikes lined up at a converted ISO container with a fuel pump at the one end, and a fuel tank inside. At the back, a generator running off the same fuel is powering the whole contraption. Quite a handy way of distributing fuel to rural areas. Also, as at most Angolan filling stations, there is a well with potable water. We fill up our tanks and our bottles.

Every male around here (and in the Congos, as we later noticed) has a machete that goes everywhere with him, like this guy on the right. It must be an initiation gift when they come of age. The luggage rack seems to offer a handy storage place.

Later in the afternoon, we almost miss this great fresco of Fidel Castro, Agostinho Neto and Leonid Breznev. The central characters in the MPLAs ascension to power here.

Clouds gather overhead as we approach Lubango. It looks threatening but we miss the rain.

Unfortunately we don’t miss nightfall as we enter the outskirts of Lubango, and it turns out to be quite a big town. It’s too late to look around for accommodation, so we turn to T4A. There are not many options, and only one offers camping: Casper Lodge.